Monads

After Monoids, Applicatives and Functors, we are ready to learn what Monads are. But, instead of starting with the monadic class definition, let’s start by an example that is actually using monads in a hidden way.

> {-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

> module Monads where

> import qualified Control.Monad.State.Lazy as ST

> import Control.Monad.State.Lazy hiding (State)

>

> import Data.Map hiding (lookup)A Simple Evaluator

Consider the following simple language of expressions that are built up from integer values using a division operator:

> data Expr = Val Int

> | Div Expr Expr

> deriving (Show)Such expressions can be evaluated as follows:

> eval1 :: Expr -> Int

> eval1 (Val n) = n

> eval1 (Div x y) = eval1 x `div` eval1 yHowever, this function doesn’t take account of the possibility of division by zero, and will produce an error in this case.

ghci> eval1 (Div (Val 1) (Val 0))

*** Exception: divide by zero In order to deal with this explicitly, we can use the Maybe type

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just ato define a safe version of division

> safeDiv :: Int -> Int -> Maybe Int

> safeDiv n m = if m == 0 then Nothing else Just (n `div` m)and then modify our evaluator as follows:

> type Exception a = Maybe a

>

> eval1' :: Expr -> Exception Int

> eval1' (Val n) = Just n

> eval1' (Div x y) = do n1 <- eval1' x

> n2 <- eval1' y

> n1 `safeDiv` n2

> (>>=) :: Maybe a -> (a -> Maybe b) -> Maybe b

Q: What happens now to our previous exception?

ghci> eval1' (Div (Val 1) (Val 0))Goal: Simplify eval1'. Let’s try to use the fact that Maybe is an applicative to simplify the definition of eval1':

eval :: Expr -> Maybe Int

eval (Val n) = pure n

eval (Div x y) = pure safeDiv <*> eval x <*> eval yWe are in a good direction, but the above does not type check… safediv has type Int -> Int -> Maybe Int, whereas in the above context a function of type Int -> Int -> Int is required. Replacing pure safediv by another function would not help either, because this function would need to have type Maybe (Int -> Int -> Int), which does not provide any means to indicate failure when the second integer argument is zero.

So, eval does not fit the pattern of effectful programming that is captured by applicative functors. They both treat Maybe to indicate failure, yet, applicatives reason about pure functions, while safeDiv observes failure depending on its arguments.

To simplify the nested tuples in eval let’s abstact away the common pattern that

- performs a case analysis on a value of a

Maybetype, - maps

NothingtoNothing, and - maps

Just xto some result depending uponx.

Abstract this pattern directly gives a new sequencing operator that we write as (>>=):

(>>=) :: Maybe a -> (a -> Maybe b) -> Maybe b

m >>= f = case m of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just x -> f xReplacing the use of case analysis by pattern matching gives a more compact definition for this operator:

(>>=) :: Maybe a -> (a -> Maybe b) -> Maybe b

Nothing >>= _ = Nothing

(Just x) >>= f = f xThat is, if the first argument is Nothing then the second argument is ignored and Nothing is returned as the result. Otherwise, if the first argument is of the form Just x, then the second argument is applied to x to give a result of type Maybe b.

The (>>=) operator avoids the problem of nested tuples of results because the result of the first argument is made directly available for processing by the second, rather than being paired up with the second result to be processed later on. In this manner, (>>=) integrates the sequencing of values of type Maybe with the processing of their result values. The function (>>=) is read as bind because is nothing fails, the second argument binds the result of the first.

Using (>>=), our evaluator can now be rewritten as:

> eval (Val n) = Just n

> eval (Div x y) = eval x >>= (\n ->

> eval y >>= (\m ->

> safeDiv n m

> )

> )The case for division can be read as follows: evaluate x and call its result value n, then evaluate y and call its result value m, and finally combine the two results by applying safeDiv. In fact, the scoping rules for lambda expressions mean that the parentheses in the case for division can freely be omitted.

Generalising from this example, a typical expression built using the (>>=) operator has the following structure:

m1 >>= \x1 ->

m2 >>= \x2 ->

...

mn >>= \xn ->

f x1 x2 ... xnThat is, evaluate each of the expression m1, m2,…,mn in turn, and combine their result values x1, x2,…, xn by applying the function f. The definition of (>>=) ensures that such an expression only succeeds (returns a value built using Just) if each mi in the sequence succeeds.

In other words, the programmer does not have to worry about dealing with the possible failure (returning Nothing) of any of the component expressions, as this is handled automatically by the (>>=) operator.

Haskell provides a special notation for expressions of the above structure, allowing them to be written in a more appealing form:

do x1 <- m1

x2 <- m2

...

xn <- mn

f x1 x2 ... xnThis is the same notation that is also used for programming with IO. As in this setting, each item in the sequence must begin in the same column, and xi <- mi can be abbreviated by mi if its result value xi is not required.

Hence, for example, our evaluator can be redefined as:

eval (Val n) = Just n

eval (Div x y) = do n <- eval x

m <- eval y

safediv n mQ: Show that the version of eval defined using (>>=) is equivalent to our original version, by expanding the definition of (>>=).

Monad is a typeclass

The do notation for effects is not specific to the Maybe or IO type, but can be used with any applicative type that forms a monad. In Haskell, the concept of a monad is captured by the following built-in declaration:

class Applicative m => Monad m where

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

return :: a -> m a

return = pureThat is, a monad is an applicative type m that supports return and (>>=) functions of the specified types. The default definition return = pure means that return is normally just another name for the applicative function pure, but can be overridden in instances declarations if desired.

The function return is included in the Monad class for historical reasons, and to ensure backwards compatibility with existing code, articles and textbooks that assume the class declaration includes both return and (>>=) functions.

The Maybe monad

It is now straightforward to make Maybe into a monadic type:

instance Monad Maybe where

-- return :: a -> Maybe a

return = pure

-- (>>=) :: Maybe a -> (a -> Maybe b) -> Maybe b

x >>= f = case x of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just y -> f yIt is because of this declaration that the do notation can be used to sequence Maybe values. In the next few sections we give some further examples of types that are monadic, and the benefits that result from recognising and exploiting this fact.

The List Monad

As with applicatives, maybe represents exceptions and lists non-determinism. We saw how the (monadic) do notation propagates exceptions on maybe values.

Q: Lets define the instance monad for lists.

instance Monad [] where

-- return :: a -> [a]

return x = [x]

-- (>>=) :: [a] -> (a -> [b]) -> [b]

[] >>= f = []

(x:xs) >>= f = f x {- :: [b] -}++ (xs >>= f) {- :: [b]-}

xs >>= f = concatMap f xs (Aside: in this context, [] denotes the list type [a] without its parameter.) That is, return simply converts a value into one result containing that value, while (>>=) provides a means of combining computations that may produce multiple results: xs >>= f applies the function f to each of the results in the list xs to give a nested list of results, which is then concatenated to give a single list of results.

As a simple example of the use of the list monad, a function that returns all possible ways of pairing elements from two lists can be defined using the do notation as follows:

> -- pairs :: [a] -> [b] -> [(a,b)]

> pairs xs ys = do x <- xs

> y <- ys

> return (x, y)Q: What is the value of

pairs [1,2,3] "cat"Q: What is the value of

pairs [1,2,3] ["cat"]Q: Write pairs using the bind operator.

That is, consider each possible value x from the list xs, and each value y from the list ys, and return the pair (x,y). It is interesting to note the similarity to how this function would be defined using the list comprehension notation:

pairs xs ys = [(x, y) | x <- xs, y <- ys]or in Python syntax:

def pairs(xs, ys): return [(x,y) for x in xs for y in ys]In fact, there is a formal connection between the do notation and the comprehension notation. Both are simply different shorthands for repeated use of the (>>=) operator for lists. Indeed, the language Gofer that was one of the precursors to Haskell permitted the comprehension notation to be used with any monad. For simplicity however, Haskell only allows the comprehension notation to be used with lists.

Q: Can you write the applicativ andTable using do nation?

andTable = (pure (&&)) <*> [True,False] <*> [True, False]> andTable :: Monad m => m Bool -> m Bool -> m Bool

> andTable xs ys

> = do x <- xs

> y <- ys

> return (x && y) Lets see how this computes!

andTable

= do x <- [True, False]

y <- [True, False]

return (x && y)

-- bind notation

= ([True, False] >>= (\x ->

([True, False] >>= (\y ->

return (x && y)

)))

-- concatMap on x

= (\x ->

([True, False] >>= (\y ->

return (x && y)

))) True

++ (\x ->

([True, False] >>= (\y ->

return (x && y)

))) False

-- apply

= [True, False] >>= (\y ->

return (True && y)

)

++ [True, False] >>= (\y ->

return (False && y)

)

-- concatMap on y

= (\y ->

return (True && y)

) True

++ (\y ->

return (True && y)

) False

++ (\y ->

return (False && y)

) True

++ (\y ->

return (False && y)

) False

-- apply

= return (True && True)

++ return (True && False)

++ return (False && True)

++ return (False && False)

-- booleans

= return True

++ return False

++ return False

++ return False

-- return x = [x]

= [True]

++ [False]

++ [False]

++ [False]

-- appending

= [True, False, False, False]Imperative Functional Programming

Consider the following problem. I have a (finite) list of values, e.g.

vals0 :: [Char]

vals0 = ['d', 'b', 'd', 'd', 'a']that I want to canonize into a list of integers, where each distinct value gets the next highest number. So I want to see something like

ghci> canonize vals0

[0, 1, 0, 0, 2]similarly, I want:

ghci> canonize ["zebra", "mouse", "zebra", "zebra", "owl"]

[0, 1, 0, 0, 2]Q: How would you write canonize in Python?

Q: How would you write canonize in Haskell?

Not very clean! Next let’s see how you can get the stateful benefits on imperative programming in Haskell using a state monad and how IO is just a special case of the state monad.

The State Monad

Now let us consider the problem of writing functions that manipulate some kind of state, represented by a type whose internal details are not important for the moment:

type State = ...The most basic form of function on this type is a state transformer (abbreviated by ST), which takes the current state as its argument, and produces a modified state as its result, in which the modified state reflects any side effects performed by the function:

type ST = State -> StateIn general, however, we may wish to return a result value in addition to updating the state. For example, a function for incrementing a counter may wish to return the current value of the counter. For this reason, we generalise our type of state transformers to also return a result value, with the type of such values being a parameter of the ST type:

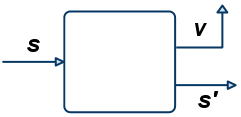

> type ST a = State -> (a, State)Such functions can be depicted as follows, where s is the input state, s' is the output state, and v is the result value:

alt text

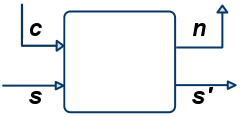

The state transformer may also wish to take argument values. However, there is no need to further generalise the ST type to take account of this, because this behaviour can already be achieved by exploiting currying. For example, a state transformer that takes a character and returns an integer would have type Char -> ST Int, which abbreviates the curried function type

Char -> State -> (Int, State)depicted by:

alt text

Returning to the subject of monads, it is now straightforward to make ST into an instance of a monadic type:

instance Monad ST where

-- return :: a -> ST a

return x = \s -> (x,s)

-- (>>=) :: ST a -> (a -> ST b) -> ST b

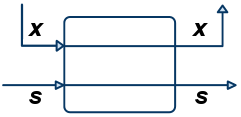

st >>= f = \s -> let (x,s') = st s in f x s'That is, return converts a value into a state transformer that simply returns that value without modifying the state:

alt text

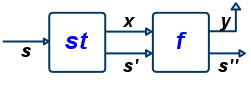

In turn, (>>=) provides a means of sequencing state transformers: st >>= f applies the state transformer st to an initial state s, then applies the function f to the resulting value x to give a second state transformer (f x), which is then applied to the modified state s’ to give the final result:

alt text

Note that return could also be defined by return x s = (x,s). However, we prefer the above definition in which the second argument s is shunted to the body of the definition using a lambda abstraction, because it makes explicit that return is a function that takes a single argument and returns a state transformer, as expressed by the type a -> ST a: A similar comment applies to the above definition for (>>=).

We conclude this section with a technical aside. In Haskell, types defined using the type mechanism cannot be made into instances of classes. Hence, in order to make ST into an instance of the class of monadic types, in reality it needs to be redefined using the data mechanism, which requires introducing a dummy constructor (called S for brevity):

Technicallity: In Haskell, types defined using the type mechanism cannot be made into instances of classes. Hence, in order to make ST into an instance of the class of monadic types, in reality it needs to be redefined using the data or newtype mechanism, which requires introducing a dummy constructor (called S for brevity):

> data ST0 a = S0 (State -> (a, State))

> deriving (Functor)It is convenient to define our own application function for this type, which simply removes the dummy constructor:

> apply0 :: ST0 a -> State -> (a, State)

> apply0 (S0 f) s0 = f s0In turn, ST0 is now defined as a monadic type as follows:

> instance Applicative ST0 where

> -- pure :: a -> ST0 a

> pure x = S0 (\s -> (x, s))

> -- (<*>) :: ST0 (a -> b) -> ST0 a -> ST0 b

> f <*> x = S0 (\s -> let (f',s') = apply0 f s in

> let (x',s'') = apply0 x s' in

> (f' x',s''))

>

> instance Monad ST0 where

> -- (>>=) :: ST0 a -> (a -> ST0 b) -> ST0 b

> st >>= f = S0 ( \s -> let (x, s') = apply0 st s in

> apply0 (f x) s'

> )A simple example

Intuitively, a value of type ST a (or ST0 a) is simply an action that returns an a value. The sequencing combinators allow us to combine simple actions to get bigger actions, and the apply0 allows us to execute an action from some initial state.

Q: To get warmed up with the state-transformer monad, lets write a simple sequencing combinator

(>>) :: Monad m => m a -> m b -> m bwhich, in a nutshell, a1 >> a2 takes the actions a1 and a2 and returns the mega action which is a1-then-a2-returning-the-value-returned-by-a2.

Next, lets see how to implement a “global counter” in Haskell, by using a state transformer, in which the internal state is simply the next integer

> type State = IntIn order to generate the next integer, we define a special state transformer that simply returns the current state as its result, and the next integer as the new state:

type State = Int

data ST0 a = S0 (State -> (a, State))> fresh :: ST0 Int

> fresh = S0 f

> where

> f :: Int -> (Int, Int)

> f x = (x, x+1)

>

> freshName :: ST0 String

> freshName = S0 f

> where

> f :: Int -> (String, Int)

> f x = ("Name: " ++ show x, x+1)Note that fresh is a state transformer (where the state is itself just Int), that is an action that happens to return integer values.

Q: What does the following evaluate to?

ghci> apply0 fresh 0Q: Consider the function surprise defined as:

> surprise1 =

> fresh >>= \_ ->

> fresh >>= \_ ->

> fresh >>= \_ ->

> freshNameIndeed, we are just chaining together four fresh actions to get a single action that “bumps up” the counter by 4. That is, the following versions of surprise are also equivalent:

> surprise1' = do

> fresh

> fresh

> fresh

> fresh

>

> surprise1'' =

> fresh >> fresh >> fresh >> freshNow, the (>>=) sequencer is kind of like (>>) only it allows you to “remember” intermediate values that may have been returned. Similarly,

return :: a -> ST0 atakes a value x and yields an action that doesnt actually transform the state, but just returns the same value x. So, putting things together, how do you think this behaves?

> surprise2 =

> fresh >>= \n1 ->

> freshName >>= \n2 ->

> fresh >>

> fresh >>

> return (n1, n2)Q: What does the following evaluate to?

ghci> apply0 surprise2 0Of course, the do business is just nice syntax for the above:

> surprise2' = do

> fresh

> n1 <- fresh

> n2 <- fresh

> fresh

> fresh

> return (n1, n2)is just like surprise2.

A more interesting example

By way of an example of using the state monad, let us define a type of binary trees whose leaves contains values of some type a:

> data Tree a = Leaf a

> | Node (Tree a) (Tree a)

> deriving (Eq, Show)Here is a simple example:

> tree :: Tree Char

> tree = Node (Node (Leaf 'a') (Leaf 'b')) (Leaf 'c')Now consider the problem of defining a function that labels each leaf in such a tree with a unique or “fresh” integer, for example, returning the following:

> tree' = Node (Node (Leaf ('a', 0)) (Leaf ('b', 1))) (Leaf ('c', 2))This can be achieved by taking the next fresh integer as an additional argument to the function, and returning the next fresh integer as an additional result, for instance, as shown below:

> mlabel :: Tree a -> ST0 (Tree (a,Int))

> mlabel (Leaf v) = do

> n <- fresh

> return (Leaf (v, n))

> mlabel (Node l r) = do

> l' <- mlabel l -- ::ST0 (Tree (a, Int))

> r' <- mlabel r

> return (Node l' r')Note that the programmer does not have to worry about the tedious and error-prone task of dealing with the plumbing of fresh labels, as this is handled automatically by the state monad.

Finally, we can now define a function that labels a tree by simply applying the resulting state transformer with zero as the initial state, and then discarding the final state:

> label :: Tree a -> Tree (a, Int)

> label t = fst (apply0 (mlabel t) 0)For example, label tree gives the following result:

ghci> label tree

Node (Node (Leaf ('a', 0)) (Leaf ('b',1))) (Leaf ('c', 2))Q: Define a function app :: (State -> State) -> ST0 State, such that fresh can be redefined by fresh = app (+1).

Q: Define a function run :: ST0 a -> State -> a, such that label can be redefined by label t = run (mlabel t) 0.

The Generic State Transformer

Let us use our generic state monad to rewrite the tree labeling function from above. The generic monad is defined in the Control.Monad.State.Lazy and, mush like our definition takes two arguments: one for state and one for the result

ST.State s a Note that the actual type definition of the generic transformer is hidden from us, so we must use only the publicly exported functions: get, put and runState (in addition to the monadic functions we get for free.)

Recall the action that returns the next fresh integer. Using the generic state-transformer, we write it as:

> freshS :: ST.State Int Int

> freshS = do n <- get

> put (n+1)

> return nNow, the labeling function is straightforward

> mlabelS :: Tree a -> ST.State Int (Tree (a,Int))

> mlabelS (Leaf x) = do n <- freshS

> return (Leaf (x, n))

> mlabelS (Node l r) = do l' <- mlabelS l

> r' <- mlabelS r

> return (Node l' r')Easy enough!

ghci> runState (mlabelS tree) 0

(Node (Node (Leaf ('a', 0)) (Leaf ('b', 1))) (Leaf ('c', 2)), 3)We can execute the action from any initial state of our choice

ghci> runState (mlabelS tree) 1000

(Node (Node (Leaf ('a',1000)) (Leaf ('b',1001))) (Leaf ('c',1002)),1003)Now, whats the point of a generic state transformer if we can’t have richer states.

Let’s now count the frequency of each leaf value appears in the tree.

> tree2 = Node (Node (Leaf 'a') (Leaf 'b'))

> (Node (Leaf 'a') (Leaf 'c'))ghci> let tree2 = Node tree tree

ghci> let (tree2', s) = runState (mlabelM tree) $ M 0 empty

ghci> tree2'

Node (Node (Leaf ('a', 0)) (Leaf ('b', 1)))

(Node (Leaf ('a', 2)) (Leaf ('c', 3)))

ghci> s

M {index = 4, freq = fromList [('a',2),('b',1),('c',1)]}Define your state so that it has now two elements:

- each node gets a new label (as before),

- the state also contains a map of the frequency with which each leaf value appears in the tree.

Thus, our state will now have two elements, an integer denoting the next fresh integer, and a Map a Int denoting the number of times each leaf value appears in the tree.

> data MyState k = M { index :: Int

> , count :: [(k, Int)]}

> deriving (Eq, Show)We write an action that returns the next fresh integer as

> freshM :: ST.State (MyState k) Int

> freshM = do

> s <- get

> let n = index s

> put $ s { index = n + 1 }

> return nSimilarly, we want an action that updates the frequency of a given element k

> updFreqM :: Ord k => k -> ST.State (MyState k) ()

> updFreqM k = do

> M i c <- get -- c :: [(k, Int)]

> case lookup k c of

> Just ki -> put (M i ((k, ki+1):c))

> Nothing -> put (M i ((k,1):c)) And with these two, we are done

> mlabelM :: Ord k => Tree k

> -> ST.State (MyState k) (Tree (k, Int))

> mlabelM (Leaf v) = do

> n <- freshM

> updFreqM v

> return (Leaf (v,n))

>

> mlabelM (Node l r) = do

> l' <- mlabelM l

> r' <- mlabelM r

> return (Node l' r')Now, our initial state will be something like

> initM = error "Define me!"In short, State makes global variables (or “statefull” programming) really easy.

The IO Monad

Recall that interactive programs in Haskell are written using the type IO a of “actions” that return a result of type a, but may also perform some input/output.

Sounds familiar?

A number of primitives are provided for building values of this type, including:

return :: a -> IO a

(>>=) :: IO a -> (a -> IO b) -> IO b

getChar :: IO Char

putChar :: Char -> IO ()The use of return and (>>=) means that IO is monadic, and hence that the do notation can be used to write interactive programs. For example, the action that reads a string of characters from the keyboard can be defined as follows:

getLine :: IO String

getLine = do x <- getChar

if x == '\n' then

return []

else

do xs <- getLine

return (x:xs)It is interesting to note that the IO monad can be viewed as a special case of the state monad, in which the internal state is a suitable representation of the “state of the world”:

type World = ...

type IO a = World -> (a, World)or

type IO a = ST.State World aThat is, an action can be viewed as a function that takes the current state of the world as its argument, and produces a value and a modified world as its result, in which the modified world reflects any input/output performed by the action. In reality, Haskell’s compiler GHC implement actions in a more efficient manner, but for the purposes of understanding the behaviour of actions, the above interpretation can be useful.

Derived Primitives

An important benefit of abstracting out the notion of a monad into a single typeclass, is that it then becomes possible to define a number of useful functions that work in an arbitrary monad.

We’ve already seen this in the pairs function

pairs xs ys = do

x <- xs

y <- ys

return (x, y)What do you think the type of the above is ? (I left out an annotation deliberately!)

ghci> :t pairs

pairs: (Monad m) => m a -> m b -> m (a, b)It takes two monadic values and returns a single paired monadic value. Be careful though! The function above will behave differently depending on what specific monad instance it is used with! If you use the Maybe monad

ghci> pairs (Nothing) (Just 'a')

Nothing

ghci> pairs (Just 42) (Nothing)

Just 42

ghci> pairs (Just 2) (Just 'a')

Just (2, a)this generalizes to the list monad

ghci> pairs [] ['a']

[]

ghci> pairs [42] []

[]

ghci> pairs [2] ['a']

[(2, a)]

ghci> pairs [1,2] "ab"

[(1,'a') , (2, 'a'), (1, 'b'), (2, 'b')]However, the behavior is quite different with the IO monad

ghci> pairs getChar getChar

40('4','0')Q: What is the type of foo defined as:

> foo f z = do x <- z

> return (f x)Whoa! This is actually very useful, because in one-shot we’ve defined a map function for every monad type!

ghci> foo (+1) [0,1,2]

[1, 2, 3]

ghci> foo (+1) (Just 10)

Just 11

ghci> foo (+1) Nothing

NothingThus, every Monad also is a Functor! Which we already know, because of transitivity!

instance (Functor m) => Applicative m where

instance (Applicative m) => Monad m whereQ: Consider the function baz defined as:

> baz mmx = do mx <- mmx

> x <- mx

> return (x+1)Q: What does baz [[1, 2], [3, 4]] return?

[1, 3], [1, 4], [2, 3], [2, 4]][1, 2, 3, 4][[1, 3], [2, 4]][]Type error

This above notion of concatenation generalizes to any monad:

join :: Monad m => m (m a) -> m a

join mmx = do mx <- mmx

x <- mx

return xAs a final example, another usefull function is mapM which maps a list of arguments to a monadic action, collecting their results:

mapM :: Monad m => (a -> m b) -> [a] -> m [b]

mapM _ [] = return []

mapM f (x:xs) = do y <- f x

ys <- mapM f xs

return (y:ys)Monads as Programmable Semicolon

It is sometimes useful to sequence two monadic expressions, but discard the result value produced by the first:

(>>) :: Monad m => m a -> m b -> m b

mx >> my = do {_ <- mx;

y <- my;

return y}For example, in the state monad the (>>) operator is just normal sequential composition, written as ; in most languages.

Indeed, in Haskell the entire do notation, with or without ; is just syntactic sugar for (>>=) and (>>). For this reason, we can legitimately say that Haskell has a programmable semicolon.

The Monad Laws

Earlier we mentioned that the notion of a monad requires that the return and (>>=) functions satisfy some simple properties. The first two properties concern the link between return and (>>=):

return x >>= f = f x -- (1)

mx >>= return = mx -- (2)Intuitively, equation (1) states that if we return a value x and then feed this value into a function f, this should give the same result as simply applying f to x. Dually, equation (2) states that if we feed the results of a computation mx into the function return, this should give the same result as simply performing mx. Together, these equations express — modulo the fact that the second argument to (>>=) involves a binding operation — that return is the left and right identity for (>>=).

The third property concerns the link between (>>=) and itself, and expresses (again modulo binding) that (>>=) is associative:

(mx >>= f) >>= g = mx >>= (\x -> (f x >>= g)) -- (3)Note that we cannot simply write mx >>= (f >>= g) on the right hand side of this equation, as this would not be type correct.

As an example of the utility of the monad laws, let us see how they can be used to prove a useful property of the liftM:

liftM f mx = do { x <- mx ; return (f x) }Namely, that it distributes over the composition operator for functions, in the sense that:

liftM (f . g) = liftM f . liftM gThis equation generalises the familiar distribution property of map from lists to an arbitrary monad. In order to verify this equation, we first rewrite the definition of liftM using (>>=): That is, we change the definition into

liftM f mx = mx >>= \x -> return (f x)Now the distribution property can be verified as follows:

(liftM f . liftM g) mx

= {- applying . -}

liftM f (liftM g mx)

= {- applying the second liftM -}

liftM f (mx >>= \x -> return (g x))

= {- applying liftM -}

(mx >>= \x -> return (g x)) >>= \y -> return (f y)

= {- equation (3) -}

mx >>= (\z -> (return (g z) >>= \y -> return (f y)))

= {- equation (1) -}

mx >>= (\z -> return (f (g z)))

= {- unapplying . -}

mx >>= (\z -> return ((f . g) z)))

= {- unapplying liftM -}

liftM (f . g) mxQ: Show that the maybe monad satisfies equations (1), (2) and (3).

A fancy monad example

Given the type

> data Exp a = EVar a | EVal Int | EAdd (Exp a) (Exp a)of expressions built from variables of type a, show that this type is monadic by completing the following declaration:

> instance Functor Exp where

> -- fmap :: (a -> b) -> Exp a -> Exp b

> fmap f (EVar x) = error "Define me!"

> fmap f (EVal n) = error "Define me!"

> fmap f (EAdd x y) = error "Define me!"

>

> instance Applicative Exp where

> -- pure :: a -> Exp a

> pure x = error "Define me!"

>

> -- (<*>) :: Exp (a -> b) -> Exp a -> Exp b

> ef <*> e = error "Define me!"

>

>

> instance Monad Exp where

> -- return :: a -> Expr a

> return x = error "Define me!"

>

> -- (>>=) :: Exp a -> (a -> Exp b) -> Exp b

> (EVar x) >>= f = error "Define me!"

> (EVal n) >>= f = error "Define me!"

> (EAdd x y) >>= f = error "Define me!"Hint: think carefully about the types involved.

Q: What does the (>>=) operator for this type do?

Further Reading

The subject of monads is a large one, and we have only scratched the surface here. If you are interested in finding out more, two suggestions for further reading would be to look at “monads with a zero a plus” (which extend the basic notion with two extra primitives that are supported by some monads), and “monad transformers” (which provide a means to combine monads). For a more in-depth exploration of the IO monad, see Simon Peyton Jones’ excellent article on the “awkward squad”.

Status Check

We saw how one can use monads in Haskell to enjoy all the benefits of imprerative programming (i.e., state and input/output) while in the back everything is functional (i.e., no side effects).

The benefit: the monadic type signatures explicitely capture the effects of your program since most effects are actually monads (“The essence of functional programming”). Remember from out first lecture notes: The following functions are pure:

fib :: Int -> Int

allRightTriangles :: Int -> [(Int, Int, Int)]

id :: a -> awhile the following have effects:

putStrLn :: String -> IO ()

updFreqM :: Ord k => k -> ST.State (MyState k) ()

eval :: Expr -> Exception IntThe common first application of monadic programming is parsing. For example, see sections 3 and 7 of the following article, which concerns the monadic nature of functional parsers, where a parser is described as string (i.e., state) transformer

type Parser a = String -> [(a,String)]But due to lack of time, we will not see this application. Instead let’s take a quick look on proving program correctness!